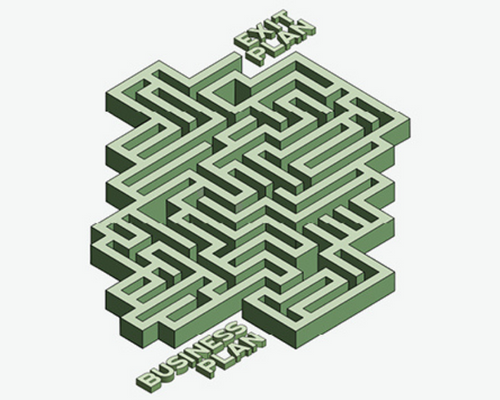

The means to an end

August 2022

By Robert Hoberman of Hoberman & Lesser for Rapaport Magazine

When the time comes to leave your company in new hands, having an exit strategy in advance can save you money and stress.

You probably invested a lot of time and energy in planning the launch of your jewelry company. The opening was likely a special day for you, your family, and your partner or partners. Eventually, though, the day will come when you exit the business. If you’ve planned properly, that day can also be a special one. A big question to consider is: Will you be able to go out on your terms — i.e., optimize the outcome for yourself, your family, your partners and your employees — or be forced into a less-than-optimal situation?

Only a relatively few entrepreneurs actually know how and when they will leave their businesses. An unsolicited yet attractive offer from a competitor may arrive. You, a partner or a spouse may experience a dramatic personal or health event. There may be a change in the competitive, legal or taxation landscapes, prompting you to reconsider your strategy. These scenarios and others highlight why preparing for your exit in advance is the best way to maximize the chances for a successful transition.

A little forethought goes a long way

Many jewelry firms are closely held companies — ones owned by an individual or a small group of shareholders. The principals are often family members or long

-term friends who have worked for many years to build a thriving business. But although the company is often the owners’ largest asset, most owners give little thought to the process of selling. This can make them vulnerable to mistakes that could leave serious money on the table.

-term friends who have worked for many years to build a thriving business. But although the company is often the owners’ largest asset, most owners give little thought to the process of selling. This can make them vulnerable to mistakes that could leave serious money on the table.

Some 41% of business owners expect to exit their companies by 2025, according to a 2020 survey by financial advisory firm UBS. While the survey covered a wide swath of industries, it found that more than half the respondents planning to exit intended to sell their companies — and of those, 48% had no strategy for doing so.

When a business goes up for sale, would-be purchasers usually have a set of conditions the sellers must meet before turning over their shares. Such conditions

include covenants not to compete, employment agreements, and confirmation that there are no undisclosed litigation issues pending, among other things — all of which require time and effort to prepare.

Having accurate records is critical to the sale process. Firms with less than $10 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) are often short on capital, according to the 2021 Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Report, and that shortage can reduce their value. The buyer may also require outside capital to complete the sale, and the company will need to have thorough documentation to show the lenders.

In addition, many owners themselves have unrealistic expectations about their firms’ actual value. A valuation gap is one of the top three reasons that deals fail to close, according to investment bankers cited in the Pepperdine report; unreasonable seller demands and insufficient cash flow are the other two.

Is there ever a right time?

When you plan to sell can be significant as well, so it pays to know the present market. In 2006, purchase prices tended to be high, so a favorable sale price was a likely outcome. During 2009 and 2010, however, conditions were not as favorable, and offer prices were among the lowest in years. While the mergers-and-acquisitions business has been brisk in recent years, today’s higher interest rates may negatively impact the price one can get for one’s company. When interest rates are lower, assessments tend to show greater profitability for the company, as cash flow should be healthier and money is more readily available. Should interest rates rise, a seller can expect a lower valuation.

While no one can tell what future market conditions will be, today’s turbulence is unlikely to scuttle a carefully planned exit. Business owners can also consider alternatives such as ongoing ownership, a new partnership or merger, an employee stock-ownership plan (ESOP), or a transition plan that grooms the next generation to take the helm.

It’s personal

Exiting your business is often about a lot more than exiting your business. Getting maximum value at the time of sale depends on comprehensive wealth-planning factors such as cash flow analysis, stock options, tax minimization and retirement planning. Family and estate matters and partnership issues are also commonly part of one’s exit plan. When owners of small- to mid-sized businesses begin seriously considering the sale option, two major questions will likely come to mind: How will I replace my cash flow? And how will I live my post-business life?

Start with an objective analysis of how much you would personally owe in taxes for a business sale if you closed such a deal now. How does it compare to the tax savings you could achieve through long-range planning? Advance preparation might well save you money on income or estate taxes, expediting a successful exit. That’s why it can pay to have an accountant on your team with experience in business sales and life transitions. Other professionals to consider are a financial planner, a lawyer, a business broker, a business appraiser/valuation expert, and a banker or lending professional if third-party funding is necessary.

It is vital to have an accurate assessment of your company’s value and whether selling it will satisfy your personal and financial goals. Having an objective professional thoroughly manage the process can help ensure that the day you leave is as meaningful as the day you began.

Image: Jon Rogers@Phosphorart